"Crisis and Response: The Tohoku Disaster and What It Means for Japan’s Future"

Crisis and Response: The Tohoku Disaster and What It Means for Japan’s Future

Seventh Annual Lecture on Japanese Politics (September 20, 2011)

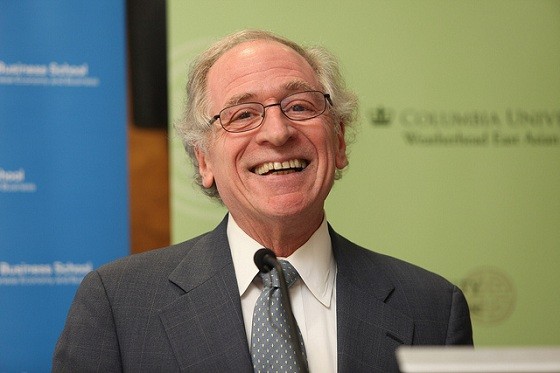

In his Seventh Annual Lecture on Japanese Politics, Gerald L. Curtis, Burgess Professor of Political Science at Columbia University, discussed the complexity of the Tōhoku disaster and its implications for the political and social fabric of Japan.

Professor Curtis began by outlining the key challenges facing the Japanese political leadership, many of these aggravated by events of the March 11 Tōhoku disaster. Newly-inaugurated Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda leads a divided parliament in which his own party, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), remains split by deep policy and factional differences. Some in the party insist that it remain faithful to its campaign manifesto despite the Tohoku disaster, and the media is bent on a sensationalist approach rather than a considered treatment of the issues Japan must deal with. As a result little focus is placed on improving the quality of current policy deliberation and debate.

Noda needs to somehow try to turn media coverage to his advantage, Curtis said. He needs a credible media strategy to rally public support for dealing with the complex of issues he inherited when he came into office earlier this month. Curtis emphasized that there has been a breakdown in communication between a risk-averse public with unrealistic expectations of both extensive government services and low taxes and leaders unwilling to tell the public that tough policy decisions are necessary. On top of that, the government’s handling of the Tōhoku disaster, especially relating to the nuclear disaster at Fukushima Daiichi, led to a dramatic loss in the government’s credibility.

Economic constraints in Japan are more severe than they were when the DPJ first took office in 2009, and the fiscally conservative Noda has since raised the prospect of a decade-long tax hike – primarily in income taxes – to fund Tōhoku’s reconstruction. However, the probability of these proposals being adopted is, according to Curtis, “about the same as Obama’s plan of deficit reduction.”

Expressing disappointment that the DPJ appears to have mostly given up on political reform, Curtis lamented the leadership’s lack of effort to create an intellectual environment by which policy debates can constructively thrive and politicians could find sources of expertise outside of the government bureaucracy. Japan lacks the policy intellectual infrastructure provided by many think tanks in the U.S. The Japanese leadership is dependent on a vertically segmented bureaucracy that adheres to a one-size-fits-all approach in dealing with problems that call for a more nuanced and locality specific response. Japan needs a better mechanism to coordinate policy between ministries and between the central and local governments. He argued that further decentralization, offering greater autonomy for local authorities vis-à-vis the central government (and its tight grip on the country’s purse strings) has to be part of a long-term strategy to restructure the Japanese government’s decision making system.

In contrast to the hesitant and inadequate central government response to the Tohoku disaster, local political leaders, the private sector and over a million volunteers responded quickly and with dedication to help the victims. The US military through Operation Tomadachi (meaning friend in Japanese) and scores of American citizens working with local non-governmental organizations in Tohoku made a significant contribution and earned the appreciation of the Japanese public.

The Tōhoku region, one of the poorest areas in Japan, and already composed of an older population, risks sinking into obscurity if the central government does not take bold actions quickly to encourage the development of the region. But the sad reality is that Tohoku which accounts for only about four percent of Japan’s GDP, and the disaster zone which amounts to less than half of that, has a crisis that is not perceived as a national crisis except for the issue of nuclear energy. Politicians in Tokyo talk about dealing with the Tohoku crisis but they are spending most of their time engaged in petty political in-fighting. One has to hope that the new Noda Administration will change this political dynamic and make Tohoku a model for a new and imaginative innovations in Japanese policy and policy making.

This event was presented by the Center on Japanese Economy and Business (CJEB) at Columbia Business School and the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University, and was moderated by Hugh Patrick, R.D. Calkins Professor of International Business Emeritus and Director of CJEB.

Image Carousel with 4 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: A packed audience of faculty, students, and media attended the event at the Kellogg Center at SIPA.

-

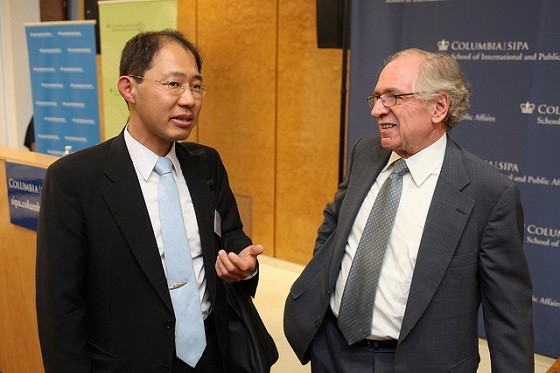

Slide 2: Professor Hugh Patrick (L) of the Center on Japanese Economy and Business was the moderator for the lecture.

-

Slide 3: Professor Curtis speaks with a member of the audience following the lecture.

-

Slide 4: image

A packed audience of faculty, students, and media attended the event at the Kellogg Center at SIPA.

Professor Hugh Patrick (L) of the Center on Japanese Economy and Business was the moderator for the lecture.

Professor Curtis speaks with a member of the audience following the lecture.