Interview with NHK’s Ayako Takada on US and Japanese media, immigrant stories, and COVID-19

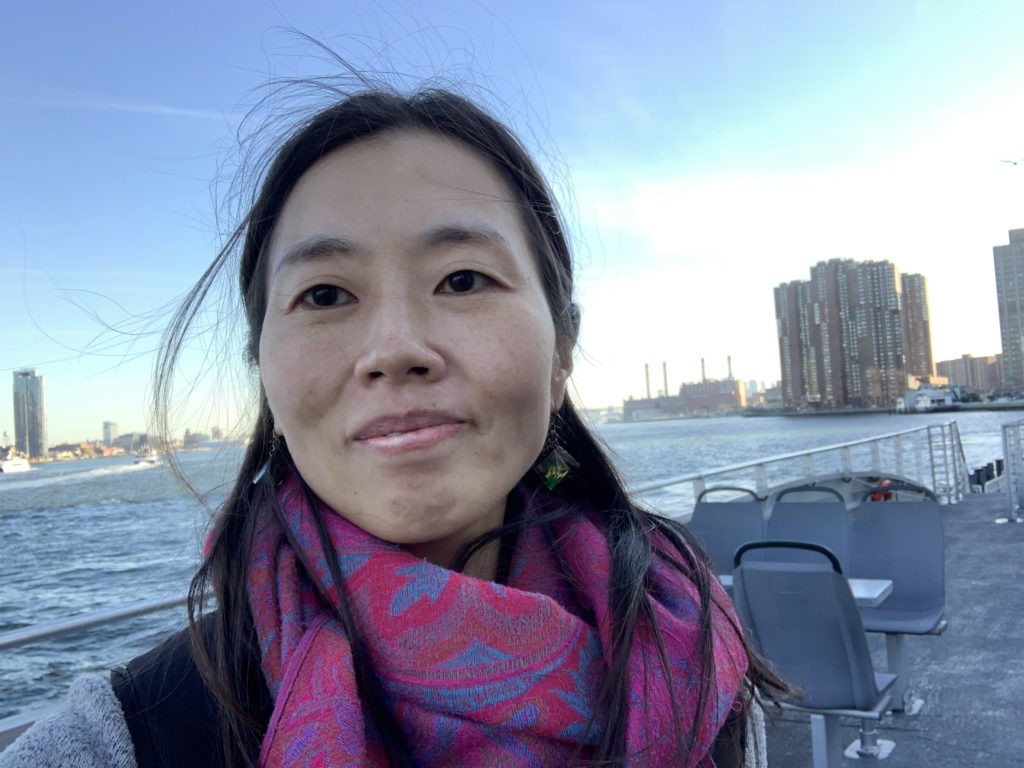

Ayako Takada is a Japanese journalist and was a WEAI professional fellow between September 2019 and January 2020. During her time in New York, she worked to design a journalism platform that builds a bridge among diverse people and began a newsletter titled “New York Immigrant Media Stories,” which documented local ethnic media and followed the early days of the spread of COVID-19 in New York. We spoke to Takada about her research and journalistic work in New York and Japan, and how that work was affected by the coronavirus pandemic.

Q. First, can you introduce yourself?

My name is Ayako Takada. I am a TV director at NHK, Japan’s public broadcaster. I hold an M.A. and am an eager student of cultural anthropology. At NHK, I have been fascinated by how people solve problems during times of upheaval. I directed documentaries on democratization of Myanmar, missing children in China, and the rise of digital media in the US. I also love covering new technologies and have covered the early but revolutionary use of telepresence robots, online education, and virtual reality. Since 2016, I have been part of a digital development team at NHK to strengthen its audience engagement. We launched a couple of short documentary video series and an open journalism system to gather viewers’ voices on what they want us to cover. Throughout my life and career, I have had a special interest in bridging people with different backgrounds and opinions with the tools developed in the media field, and the values we learn from academia.

Q: What brought you to WEAI? How did you explore your research interests while at Columbia?

I was affiliated with WEAI in 2019 and lived in New York from August 2019 to March 2020. My research theme was designing a journalism platform to build a bridge among diverse people based on quantitative field research into innovative media outlets in the US. I had been working on updating NHK’s roles and mission for a few years. When I was looking for schools where I could study, I was determined to learn how Japan and its relationship with other East Asian countries would look to non-Japanese people outside Japan, and what sort of topics are studied in a top-level institute. During my stay I was fascinated by Professor Gerald Curtis’s study on the Japanese election system and attended Professor Takako Hikotani’s course “Japanese Politics.” It was also critical that I was able to attend many seminars related to Japan and Asia hosted by the WEAI. Outside WEAI, the course “Decolonization Methodology” by Professor Paige West at the Center for the Study of Social Difference helped me reflect on how we should produce knowledge ethically. Every time I went to campus, I was surprised by how much I could update my common sense and knowledge I had accumulated in Japan.

Q: Can you speak about the newsletter you started? What inspired you to start this project and what was your intention or goal?

In February I started a weekly newsletter called “New York Immigrant Media Stories,” which talked about different ethnic media in New York—what they do, how they started and how they bridge minority communities and the broader society. I was intending to make it my platform to build relationships with ethnic media in New York, to prototype a service that embodies my mission to design a journalism platform that builds a bridge among diverse people.

In 2019, I also attended the social journalism program at the Craig Newmark School of Journalism at CUNY, which trains students to connect with and listen to the communities they cover and build actual journalistic services for them. In the “Startup Sprint” course, I learned how to connect myself with the people I cover and the audience by publishing stories regularly. In fact, many news media, including The New York Times, put so much energy into newsletters to strengthen audience engagement. I thought it would be a great way to target who would be interested in supporting immigrant media and collaborating with me or immigrant media.

I ran it as a low-profile, closed community like personal letters. I invited friends in Japan and in the US who are interested in diversity and inclusion to become readers. I wanted to start small because I didn’t want people to take it as an official project of NHK, and I wanted my freedom to communicate with my audience and update as readers wish.

I talk about the newsletter in the past tense because I had to cut short my research on it, as I had to leave New York in March when COVID-19 spread. The newsletter lasted only 10 weeks, and I shifted to writing about my own experience as a Japanese experiencing the crisis in New York and later in Tokyo. But it was a very fruitful experiment that brought many new relationships and deep conversations. Many of my readers said they would be happy to pay around 500 yen (5USD) per month. I am not only talking about money. Being sustainable is the most important challenge for journalism nowadays.

Q: Can you share any particularly memorable stories you gathered while working on your newsletter?

When I visited the studio of Bangla Patrika, a Bangladeshi media company in Long Island City, I was amazed by its positive vibes and very effective work system. Bangladeshis are the fastest-growing population in New York, with 82,351 as of 2015. In 1996, the CEO of Bangla Patrika, Abu Taher, launched a weekly newspaper with two friends, each bringing $5,000. Taher, who was born in 1968, spent his teenage years under the military regime in Bangladesh. He dreamed of coming to the US, the leader of the free world in the post-cold war era, and made his dream come true in 1992. The paper has been reporting news and stories of the Bangladeshi community for the Bangladeshi community in the US In 2014, the company launched an internet TV platform to target a young audience with different backgrounds all over the US. It produces six hours of programming daily, from news to legal advice, in both English and Bengali. As I observed Bangla Patrika’s work and content, I felt I was witnessing the history of the Bangladeshi community and New York being made and recorded. The media’s growth depends the development of the community, and the community gets a voice as it is covered by the media. I felt this was the purest form of ethnic media. The editor in chief is now a good friend of mine and he drove me to the airport when I had to leave New York on March 24.

From March 11, I decided to basically stay home. That gave me a chance to write about my great landlady Dr. Jane Howard Bond in the newsletter. She is a historian specializing in modern French history whom I met via a Columbia University housing match service. We got on very well and she even helped me understanding Black feminism for the “Decolonization Methodology” class. Her father was among the first generation of African Americans to receive PhDs and she is just amazingly smart and sharp and was always reading. One evening during the pandemic, she told me about her experience as a Black girl during World War Ⅱ in Tuskegee, Alabama. Her story was different from any books or films I have seen and made me think about the very complex history of African Americans.

Image Carousel with 3 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: Journalists at Bangla Patrika

-

Slide 2: Jane and I shared a simple home-cooked soup for her 87th birthday

-

Slide 3: On April 7, the Japanese government declared a state of emergency in seven prefectures

Journalists at Bangla Patrika

Jane and I shared a simple home-cooked soup for her 87th birthday

On April 7, the Japanese government declared a state of emergency in seven prefectures

Q: You were in New York at the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in the US and have since returned to Japan. Can you speak a bit about that experience? How did the way the US handled the situation compare to what you saw in Japan?

I experienced the declaration of state of emergency on March 13 in the US and on April 16 in Japan. I started social distancing in New York at the end of February as I heard news about how the virus was spreading in Asia and Europe. I wanted to be extremely careful because I didn’t want to get sick abroad and I lived with Jane, the 87-year-old landlady. Jane and I planned so we didn’t have to go out much and began to share the table every day. She asked me many things about Japan and my career. It was a precious gift I received during quarantine. We would watch the news every day and looked forward to the daily briefings of the New York Governor Cuomo. It was surprising how much time he spent communicating with the public and how eagerly he answered reporters’ questions. When I returned to Tokyo in late March, I was disappointed to see how little time the prime minister spends on press conferences. Cuomo was also good at promoting hand-washing, social-distancing and stay-at-home home policies. Japanese politicians and media had to import the word “social distancing” (ソーシャルディスタンス in Japanese) to talk to people, along with the other keywords the Japanese government and scientists came up with. American politicians are much better at communicating their will to the public than Japanese ones.

However, I think the US lacks effective and flexible public health policies. I worried when I saw people in New York walking around without protecting themselves with masks, even when there were bad viruses going around. I got scared and wondered why the government and citizens don’t take all necessary measures to protect themselves. Even official organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had a policy to discourage people from wearing masks. I understand it was to save medical resources, but it definitely gave people the wrong idea that masks don’t help. In Japan, masks are used to prevent the germs from jumping to the other people, as well as guarding one’s throat. I was also shocked to hear the MTA finally closed overnight in May for thorough cleaning. I hope the US will create safer and cleaner public spaces for everyone.

Q: As a journalist, can you speak about Japan’s news coverage of events–including the COVID-19 outbreak–in the US, which has since become the global epicenter for the virus? What does the Japanese public know/feel about what is going on here?

The US situation under Covid-19 has been covered quite often in many news media in Japan from various aspects. In late March and early April, many news programs introduced the voices of people in the US to give alerts, as the Japanese government seemed too soft in handling the situation. Through April and May, it became clear that the pattern in the US was far worse than in Japan, and Japanese media started to depict the US as a barometer of where the world is going.

To some, it is shocking to see how the US is failing to contain the virus, but surprisingly, I don’t see criticism of the Americans. I think the Japanese are generally very sorry about what is happening in the US because many people, regardless of their political views, like something about the US—its culture, its spirit or nature. Many people are worried about the future of the US because it has been one of the countries closest to Japan for over 70 years. At the same time, through the experience of such a close country, where they used to travel freely to, people are learning the pandemic is a global issue, and until all countries are free of it, we cannot completely relax.

Q: Similarly, what are your thoughts on the way Japanese news is covered in the US? Do you believe that US media have a good understanding of the situation in Japan? Or are there any misunderstandings you would like to address?

Generally speaking, Japan is not covered so much in the US I think it is natural when Japan has lost its miraculous economic power and become a “quiet country,” as my English teacher says. However, I sometimes wonder how the US media choose topics to cover. They reported on how Korea or Singapore or Taiwan was successful in containing the virus in late March. Similarly, Japan had a low number of cases compared to Western countries, but I never saw it on the news. Those countries had notable policies of social distancing, and Japan didn’t. Everybody, including the Japanese experts, wondered why Japan and Asian countries had a smaller number of cases. I think, instead of omitting Japan, it would be interesting to look at not only the policies, but also genes and cultures.

Although I do think the US media who have bureaus in Japan have good understanding of the situation in Japan, I feel that the American media don’t imagine what the Japanese think when they read their articles. They often criticize many things about Japan: gender balance, corporate culture and slow political decision-making. I often wonder who they are talking to and for what, especially when they say, “Japan’s number of cases is surging again,” when Japan has only 200 daily cases compared to 58,000 in the US. Sometimes I feel that they are doing it intentionally, to put pressure on the Japanese to change for the better, which actually works. And it is often the mirror effect of the Japanese media’s not being critical enough.