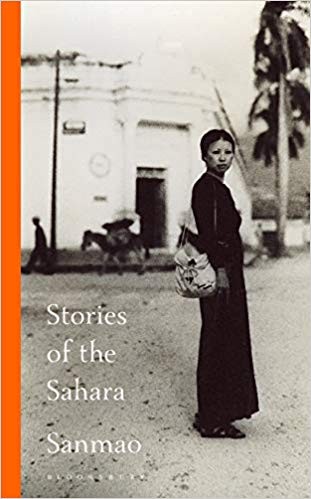

Alumni Feature: Mike Fu, translator of Stories of the Sahara by Sanmao

In 1973, a Taiwanese woman by the name of Sanmao made her way to the turbulent Spanish Sahara. She trekked through cultural and linguistic barriers, romance, solitude, and mirages, before publishing her experiences of the desert in the form of a book. Now, more than four decades after its original publication in Chinese, Sanmao’s groundbreaking 1976 debut Stories of the Sahara is getting its first English release. We spoke with Columbia alumnus and translator Mike Fu about his 2020 translation of Stories of the Sahara. The full interview follows.

To start, could you please introduce yourself?

My name is Mike Fu and I’m a writer, translator, and editor based in Brooklyn.

When were you at Columbia and what brought you here initially?

I moved to New York in 2008 to begin grad school in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at Columbia. I wrote my thesis on contemporary Chinese cinema, specifically the directorial work of Jiang Wen, under the supervision of then-faculty member Weihong Bao. After receiving my MA in 2010, I worked as the Events and Programming Coordinator at WEAI until 2013.

Can you introduce this book, Stories of the Sahara? Who is the author, Sanmao, and how would you describe her writing?

Sanmao was the pen name of an iconic writer who was immensely popular across Greater China the late 1970s and 1980s. Born in Chongqing and raised in Taiwan, she was a free-spirited young woman who studied abroad in Europe and the US and became fluent in many languages, including English and Spanish, along the way. In 1974, she settled in the Spanish Sahara and began publishing vignettes about her day-to-day life in colonial Africa with her husband José María Quero. These writings were later collected as Stories of the Sahara; each chapter is mediated through the lens of a first person narrator-protagonist, also called “Sanmao,” as she navigates a landscape both mundane and fantastical.

What initially attracted you to this book?

I encountered the book for the first time in my mid-twenties. I grew up primarily in the US and, as much as I’d like to believe otherwise, reading Chinese has always been quite draining for me. But Sanmao’s voice captivated me from the get-go. Her humor was infectious, and her sense of character and narrative flow were absolutely riveting.

The stories follow Sanmao’s experience in the Sahara Desert interacting with the people there, as well as her relationship with her Spanish husband. Can you speak about the unique experience and the challenges of translating such a culturally layered book–in this case, presenting a Chinese perspective of Spanish Sahara to English readers?

It’s indeed interesting to consider the layers of culture and language at play here. Sanmao wrote in Chinese about her experiences living among the Sahrawi, natives of the western Sahara who speak Hassaniya Arabic. Though a few simple Arabic phrases do appear in the book, Sanmao’s interactions with her husband, friends, and neighbors were all conducted in Spanish, which she rendered in Chinese for the benefit of her initial readers in Taiwan. Forty-some years later, I spent a great deal of time thinking about how best to convey her worldview and sensibilities, as much as dialogue and descriptions, into English – with some Spanish and Arabic peppered in there, of course. Figuring out how to interpret Chinese transliterations of certain proper names was especially tough.

Why is this book being translated now and why have Sanmao’s works never been translated into English before?

I was also surprised to discover there wasn’t already an English translation when I read Stories of the Sahara for the first time. I’m afraid I don’t know why the book hadn’t been translated until now. There were Japanese and Korean translations back in the 1980s, I believe, but only in the past few years has Sanmao’s work reached a wider readership, thanks to recent translations of Stories of the Sahara into Spanish, Catalan, and Dutch, as well as my own English version.

How do you think an English reader in 2020 will respond to Sanmao’s writing compared to a Chinese reader when Stories of the Sahara was first released in 1976?

I hope the contemporary English reader will be won over by her sly humor and compassionate storytelling like her first fans were. Nowadays no one bats an eye at a young Chinese woman traveling far and wide for work, study, or pleasure. The world was a different place in the 1970s and, in the Sinosphere, Sanmao was really a trailblazer. She inspired a whole generation (and then some) to live freely and search for their own truth and meaning in an increasingly complex world.

Fu will discuss his translation of Stories of the Sahara with YZ Chin at Greenlight Bookstore in Fort Greene on February 6. Click here for more information about the event.