WEAI Author Q&A: Aaron Skabelund on "Inglorious, Illegal Bastards"

We are excited to announce a recent title in the Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute book series: Inglorious, Illegal Bastards: Japan's Self-Defense Force During the Cold War, published by Cornell University Press. The book's author Aaron Herald Skabelund is Associate Professor of History at Brigham Young University.

In Inglorious, Illegal Bastards, Aaron Herald Skabelund examines how the Self-Defense Force (SDF)—the post–World War II Japanese military—and specifically the Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF), struggled for legitimacy in a society at best indifferent to them and often hostile to their very existence.

From the early iterations of the GSDF as the Police Reserve Force and the National Safety Force, through its establishment as the largest and most visible branch of the armed forces, the GSDF deployed an array of public outreach and public service initiatives, including off-base and on-base events, civil engineering projects, and natural disaster relief operations. Internally, the GSDF focused on indoctrination of its personnel to fashion a reconfigured patriotism and esprit de corps. These efforts to gain legitimacy achieved some success and influenced the public over time, but they did not just change society. They also transformed the force itself, as it assumed new priorities and traditions and contributed to the making of a Cold War defense identity, which came to be shared by wider society in Japan. As Inglorious, Illegal Bastards demonstrates, this identity endures today, several decades after the end of the Cold War.

We thank Dr. Skabelund for taking the time to discuss his book with us.

Q: First, could you share a brief history and introduction of Japan’s Self-Defense Force?

Japan’s postwar military has been the source of considerable controversy for its entire existence. After the country’s disastrous defeat in 1945, American occupation authorities sought to democratize and demilitarize Japan. US authorities dismantled the Imperial military and created a new constitution that prohibited “land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential.” Yet just three years later in 1950 after the outbreak of war on the Korean peninsula, US officials “authorized” (read “ordered”) the Japanese government to establish what Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers Douglas MacArthur called a “National Police Reserve,” a label chosen to make it seem as if the organization was not in fact an embryonic military and therefore not a violation of the constitution. Because the reestablishment of a military force, unlike in West Germany, was regarded as unconstitutional, was not openly debated, and was not part of a regional security alliance like NATO, the Self-Defense Force as it was renamed in 1954, struggled to gain acceptance from wider society. Its efforts to do so—and the experience of its individual personnel—is the focus of my book.

Legal and societal forces have also constrained the force. Although the constitution came to be interpreted to mean that Japan had the right to self-defense, these circumstances restrained its spending, weaponry, and operations. That said, as Japan’s economy grew so too did its military budget and power. By the 1970s when the economy became the second largest in the world, Japan’s defense budget became among the world’s largest even as societal pressures kept defense spending to less than 1 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.

Today, the SDF, which since 1954 is composed of three branches—ground, maritime, and air forces—that number around 250,000 members who are armed with various kinds of tremendous defensive firepower that could be put to offensive use. Further reinterpretations of the constitution have also given the force great operational latitude, including permitting collective defense. Yet the constitution has never been revised, and significant societal resistance to the SDF becoming a military in name and in more practical ways remains strong today.

Q: Can you tell us about the reputation of the SDF during the Cold War––the time period your book focuses on? What were the main factors that led the SDF to be viewed as a force of "inglorious, illegal bastards"?

Because of constitutional and societal constraints, the public has long regarded the SDF with marked suspicion, particularly from the left, but even from the right, as well as from the middle. The SDF came to be viewed as a force of “inglorious, illegal bastards,” because of three troublesome relationships: with society, with its predecessor the Imperial military, and with the US military. Wider society—on the left, right, and in the middle—has respectively viewed the force as illegal and unconstitutional, hamstrung by the constitution, and simply suspect. As the successor to the Imperial military, once again along the same political continuum, the SDF was inglorious—similar with, not enough like, and once more seen as suspicious because of connections with the pre-1945 armed forces. And in terms of the US military, Japanese across the political spectrum regarded the SDF as a bastard and were ashamed of the force’s American ancestry and its (and Japan’s) ongoing dependence on and subordinate status to this foreign military. Citizens found the US military presence on the islands in the form of bases and tens-of-thousands of military personnel to be humiliating or at the least disconcerting, though many did not think the country would be safe without US military protection so they grudgingly supported the status quo.

Q: In Inglorious, Illegal Bastards, you challenge the common perception of SDF personnel as “invisible men,” and suggest that the force was actually quite visible in society. What sorts of misconceptions surround the SDF, and how do these factor into the perception of the force?

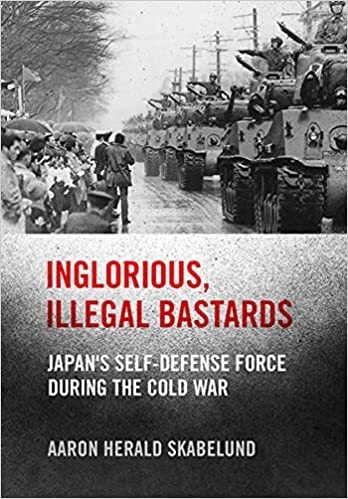

Many contemporary media observers and scholars since have suggested that the SDF and its personnel were largely invisible within and to wider society. But the force was in fact often quite visible. This is why I prefer to use the parenthetical descriptor, (in)visible men, which suggests both their invisibility and visibility. Though SDF members may have kept a lower profile than their Imperial military predecessors and contemporary foreign military counterparts, civilian political and bureaucratic leaders and force commanders sought for strategic reasons to make them as visible as possible. For example, Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru immediately sought to deploy the Police Reserve Force for disaster relief operations so that it would be regarded “with a more friendly feeling” by the public. This too was the rationale for having the SDF provide extensive support for the Sapporo Snow Festival from the early 1950s. It was also one motivation for mobilizing the force to provide logistical support for and to have individual service members compete in the 1964 Olympic Games. And it was the reason why the government had the force regularly parade through the streets of Tokyo and other major cities during the 1950s and 1960s. I selected a photograph for the cover of my book of one such parade—through central Sapporo in 1964—to illustrate this attempt to be at visible as possible.

Q: Can you share some of the highlights from your research in conducting oral history interviews with rank-and-file personnel (and others)?

Much of my research took place while I was affiliated with Hokkaido University. I was fortunate that at the time—from 2003 to 2006 and during later shorter research visits—a retired SDF member, Satō Morio (1932-2020) was a graduate student there. I visited formally and informally with Satō many times, and he introduced me to other veterans, including Irikura Shōzō, who like Satō joined the Police Reserve Force as a young man in 1950. Irikura, thanks in large part to being an editor of the Northern Corps’ newspaper, the Akashiya, for many years, possessed a vast network and happily introduced me to other veterans in Hokkaido and elsewhere. Those interviews with former rank-in-file personnel greatly enriched my book. I also conducted interviews with over a half-dozen former officers who graduated from the National Defense Academy during its early years in the 1950s. A former president of the academy kindly made those introductions.

Q: What is the reputation of the SDF like in Japan today?

The SDF is now regarded as one of the most respected and most trusted institutions in the country. This is in stark contrast to how the force was viewed by wide segments of society during the Cold War. Geopolitical change—particularly the threat of North Korea and the rise of China—has of course contributed to greater support for the SDF. But the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011 also contributed to a rise in support. Millions of people witnessed the bravery of SDF helicopter pilots as they flew over one of the radioactive nuclear reactors and tried to cool them by dropping water on them. In 2012, positive views of the SDF jumped to over 90 percent. That said, respect for the SDF does not necessarily mean the public wants Article Nine to be revised and for the force to be transformed into a military like those elsewhere.

Q: Given the current political context in Japan –– the leadership of the Liberal Democratic Party continues to advocate for the revision of Article 9 and in December of 2022 unveiled a new security strategy which includes the doubling of its military budget over the next five years, the development of counterstrike capability, and a new joint operational command in the SDF –– how might the SDF evolve as a de facto military force, and in the public imagination, in the years to come?

As a historian, I don’t like making predictions but if I had to do so I would say the SDF will continue to slowly evolve to become more of a military force less restrained in its operational latitude. This will be because of gradual reinterpretation of the constitution and a further evolution in public opinion, as we have seen over the decades, rather than because of a revision of the constitution. I don’t think we want to see the latter happen, because it would mostly likely be the result of the worsening of geopolitical tensions in East Asia and/or the Japan no longer seeing the United States as a reliable ally.