This lecture explores the life of an elite woman, raised in Beijing and educated at a missionary school during the May Fourth era. Daughter of a Beiyang reformer, wife of a Nationalist official educated at MIT, mother of an underground Communist revolutionary, she herself left no direct trace in the public record. She emerges primarily in interviews with her son, and in an unfinished and unpublished historical novel by her daughter. Filial love, household management, sexual propriety, wifely duty, maternal loyalty, domestic cosmopolitanism, and shrewd political judgment mingle in her story, raising questions about where revolution lies and how we should track its less visible effects. Her life illuminates the gendered effects of China’s long revolution, the central importance of women as symbols of the nation, and the limits of what we can know about the past.

Speaker:

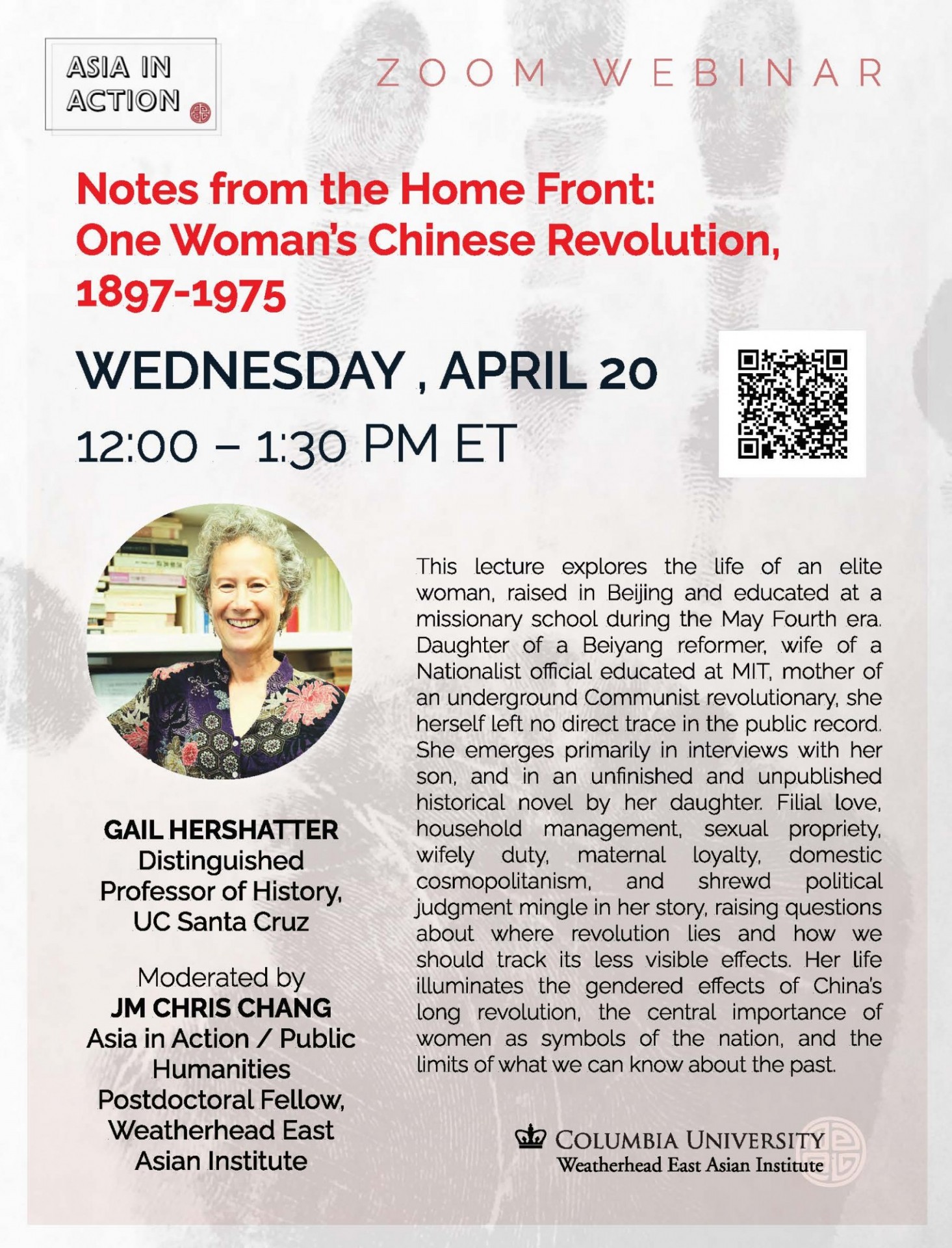

Gail Hershatter, Research Professor and Distinguished Professor Emer. of History at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Professor Hershatter is a former President of the Association for Asian Studies. Her works include The Workers of Tianjin (1986, Chinese translation 2016), Personal Voices: China Women in the 1980s (1988, with Emily Honig), Dangerous Pleasures: Prostitution in Twentieth-Century Shanghai (1997, Chinese translation 2003), Women in China’s Long Twentieth Century (2004), The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China’s Collective Past (2011; Chinese translation 2017) and Women and China’s Revolutions (2019).

Moderated by JM Chris Chang, Asia in Action / Public Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow at the Weatherhead East Asian Institute.

This event is the second in a four-part series for WEAI's Asia in Action workshop series, "Remapping the Archives: New Histories of the PRC."

Series description:

In the present moment, intensifying historical censorship in China–compounded by the lasting impacts of the pandemic–has severed access to the archive as we once knew it. The Modern China field has been forced to reckon with the possibility that access to PRC sources may soon become exceptional, and that its foreclosure portends a post-archival future. What is history without archive, or archive without history? The purpose of this four-part series is to explore promising responses by several scholars to this crisis in the archive, both as a means of illuminating new methodological directions in PRC history as well as reexamining perennial historical questions from a new aspect.

The next two events in this series are:

Wed. April 27 / 12:00 – 1:30pm

Chinese History in the Age of Big Data

LU Yi, Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Oxford with discussant Uluğ Kuzuoğlu

Abstract: Digitization facilitates censorship in Chinese archives, but it also gives us new tools to study censorship and to renew the historian's craft. This talk explores the opportunities and challenges of studying twentieth-century Chinese history in the digital age. Drawing on archival statistics and metadata from several provincial collections, it begins by taking stock of the archival landscape in contemporary China: What has been made available (and not?) It then applies the latest digital methods to query the genre of "nianpu" (chronicles) in the Chinese Communist Party historiography. Using techniques such as named entity recognition and network analysis, it reveals internal connections and textual discrepancies to raise new questions about elite politics and political communication in Mao's China. The talk will end with ideas for digital study of modern Chinese history and practical suggestions for research data management in the age of information overload and official surveillance.

--

Wed. May 4 / 12:00 – 1:30pm

Practicing Policing in China (1949-1963)

WANG Juan, Associate Professor of Political Science, McGill University

Abstract: Policemen served a pivotal role in the politics of the Mao era, yet we know little about these important historical actors. This paper draws upon rich archival records of police work reports to county authorities in western China from 1949 and 1963 to examine everyday practices of policing. In particular, I look at the reported operation of a county police department in dealing with population movement and household registrations, which served as foundations for executing policies related to social order, political prosecution, and economic redistribution. My paper analyzes these police reports with a focus on the language used, the venue and manner in which investigations were conducted, and explanations for conclusions reached. In doing so, my paper sheds light on the close connections between investigative methods, the making of bureaucrats, and narrative construction as a practice of policing.

Sponsored by WEAI.