WEAI Author Q&A: Chad Diehl’s ‘Resurrecting Nagasaki’

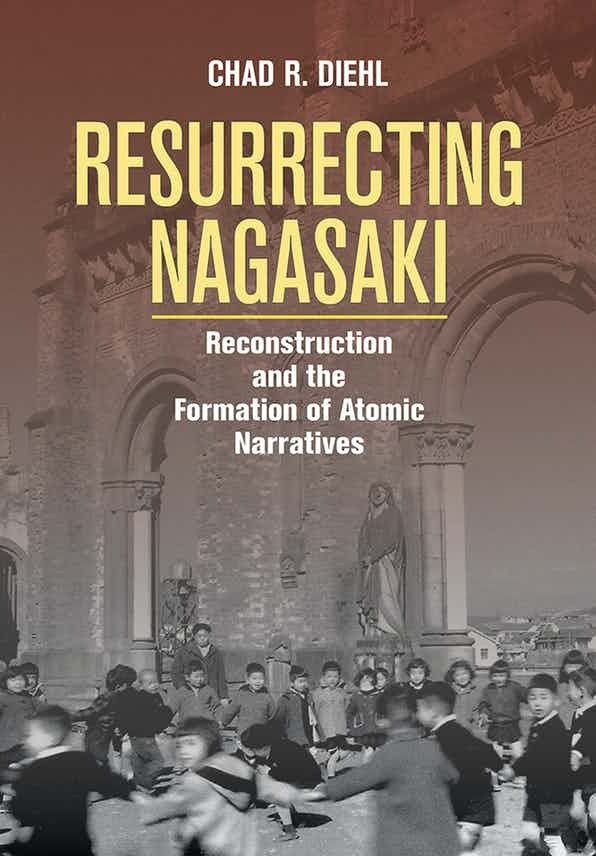

We are excited to share this exclusive interview with Chad Diehl, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia, and author of Resurrecting Nagasaki: Reconstruction and the Formation of Atomic Narratives. The book was recently published by Cornell University Press with the Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute.

In Resurrecting Nagasaki, Diehl examines the reconstruction of Nagasaki City after the atomic bombing of August 9, 1945. Diehl illuminates the genesis of narratives surrounding the bombing by following the people and groups who contributed to the city’s rise from the ashes and shaped its postwar image in Japan and the world. Municipal officials, survivor-activist groups, the Catholic community, and American occupation officials interpreted the destruction and envisioned the reconstruction of the city from different and sometimes disparate perspectives. Each group’s narrative situated the significance of the bombing within the city’s postwar urban identity in unique ways, informing the discourse of reconstruction as well as its physical manifestations in the city’s revival. Diehl’s analysis reveals how these atomic narratives shaped both the way Nagasaki rebuilt and the ways in which popular discourse on the atomic bombings framed the city’s experience for decades.

We thank Professor Diehl for taking the time to discuss his book with us.

Can you introduce yourself and how you came to study Nagasaki?

I grew up in Montana and went to college at Montana State University, where I began studying Japanese. During my junior year abroad in Kumamoto, Japan, I visited Nagasaki and became interested in the city’s history. After graduating from MSU, I lived in Nagasaki for one year on a Fulbright Graduating Senior Fellowship to research the atomic bombing, especially how survivors struggled with their trauma in the aftermath. I then went to Columbia University for my PhD, which I completed in 2011. I have since taught at several institutions and am currently an Assistant Professor, General Faculty, in the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia.

When I lived in Japan, I also became an active member of the judo community for more than three years. During the research for this book, I lived for eight months in a dormitory with some of the best judo practitioners in Japan, many of whom eventually became world champions and Olympic medalists. The experience has, in many ways, determined the path my life has taken ever since.

Why do you think that the history of Nagasaki’s bombing and reconstruction has been less well known than that of Hiroshima’s?

This is one of the main questions I am trying to provide an answer to in the book. The dominance of “Hiroshima” cannot be explained away because that city’s bombing happened first, even though that fact has bolstered its identity as the atomic-bombed city. Rather, many factors have been at play since the early postwar years, and I focus my analysis on a few of those. I look especially at the municipal policies of reconstruction in Nagasaki that downplayed the bombing, and trace how the urban identity that developed from those policies shaped atomic narratives within and about the city.

What questions about the post-bombing reconstruction led you to undertake this project?

I was first interested in understanding how the Catholics of Urakami, a district in the northern part of Nagasaki and which saw the most destruction, could view the bombing as a manifestation of God’s Providence. One leader named Nagai Takashi, who became the voice of the Catholics and eventually the entire city, argued that God had chosen the Urakami Catholics as a sacrificial lamb to end the war. From the moment I first encountered this interpretation of the bombing, I was hooked on the history of the city. As I researched the Catholic narrative of the bombing, I began to see how the reconstruction process had led a number of groups to develop different and sometimes overlapping narratives about the destruction and revival. I wanted to find out the ways in which these narratives shaped Nagasaki’s path forward as well as its image in popular memory.

What are the most significant ways that Nagasaki’s post-bombing experience differs from Hiroshima’s?

There are so many differences between the experiences of the two cities that I could not address them all in the book. One that I do cover at length, however, is how the official paths of reconstruction taken in each city created disparate urban identities. In reconstruction plans, Nagasaki officials emphasized the city’s long history as a center of international trade and culture, but Hiroshima did not have the same kind of “bright” past to revive in the postwar period. Instead, it linked its atomic destruction to the postwar peace, officially becoming the “Peace Commemoration City” from 1949. Nagasaki became the “International Cultural City.” Of course, another aspect of Nagasaki’s postwar story that differs significantly from Hiroshima’s is the presence of the Catholic community, which had a large voice in the reconstruction, in both direct and indirect ways.

What kinds of sources and archives did you consult in the course of your research?

My book draws heavily on primary sources from the 1940s-1960s, especially newspapers and other print media, as well as unpublished letters and other writings.

I found out early on in the course of my research that a lot of municipal records had burned in a fire in the 1950s, and so the city’s archives for the early postwar years were unfortunately not as useful as I had hoped. A former advisor to the Nagasaki mayor’s office also told me that nobody had yet written about the reconstruction of the city, and so there were not any additional sources or records he could point me to. This all meant that I had to write the story of Nagasaki’s postwar revival from whatever pieces of the puzzle I could track down.

The most useful archive for my work, it turned out, was a large collection of materials at the Nagai Takashi Memorial Museum, a small museum about the life of Dr. Nagai Takashi who is a key figure in my book. The museum is managed by his grandson, Nagai Tokusaburou, and to my knowledge no other non-Japanese researcher had ever been given access to the museum’s collection. I felt extremely lucky to see the materials, too, because Tokusaburou and I had known each other for more than three years before he trusted me enough to open the doors to the archival materials room. The collection included mountains of letters, journal and newspaper clippings, photographs, book manuscripts, drafts of speeches, drawings, and a variety of other documents, all related to the life of Nagai Takashi, the history of the Urakami Catholic community, and the first decade or so of reconstruction more generally.

The rarity of the collection, and the fact that the most meaningful historical monographs seem to emerge from a deep engagement with primary sources, inspired me to make the book as primary-source driven as I possible could. Even so, the Nagai archive contained so much material that I only managed to fit a small percentage of it into the book.

Reviewers have so far appreciated the amount of primary-source material that I include. However, to my surprise, one reviewer took issue with my approach and seemed to argue that junior scholars needed to prove their bona fides by referencing, instead, as many secondary sources as possible. This view naturally took me by surprise, both because I disagree with such a hierarchical approach to academic scholarship, and because I did include both Japanese and English-language secondary sources. In fact, my engagement with these other books helped frame the analysis and pace of each chapter. Of course, the book does not provide a historiographical discussion, but I never intended it to do so. In the end, I did not feel a need to flex my bookshelf, so to speak, and so I relied heavily on primary sources to guide the direction of my historical writing.

How did you decide to structure this book? What groups did you decide to focus on when telling this story?

I structured the book around the four main groups who were active in the city’s physical reconstruction and who also fashioned the city’s enduring atomic narratives: the municipal officials (many of whom also experienced the bombing), American occupation personnel, the Urakami Catholic community, and the hibakusha activists (hibakusha is the term generally used for atomic-bombing survivors). I tried to give each group its own chapter while maintaining a mostly chronological telling of the history, but every chapter includes all of the groups in some way. Chapter one focuses on the municipal officials, chapter two on the American occupation personnel, and chapter three on the Catholics. Chapter four looks at both the occupation personnel and the Catholics. Chapter five illuminates the postatomic lives of the hibakusha, especially those who became activists. Chapter six attempts to tie the threads of the book together by looking, again, at the hibakusha-led activist groups, the municipal officials, and the Catholic community.

How would you like this book to contribute to our understanding of the history of Japan in the wake of the atomic bombing?

Pointing out precisely how much Nagasaki and Hiroshima differed in their paths of recovery was one of the main inspirations for writing the book, as was showing the value of studying Nagasaki on its own terms. Nagasaki is just as important as Hiroshima is to our historical understanding of the atomic bombings and their aftermath. And, yet, the notion that only Hiroshima can offer insight into the bombings is endemic in academia, so much so that based on the amount of scholarship that has been produced about Hiroshima, the field of study related to the bombings should really be called Hiroshima Studies. It may seem like an obvious statement, and I do not mean to sound repetitive, but Hiroshima’s experience cannot speak for Nagasaki. The work done so far on Hiroshima is indeed valuable, but it should not define the trajectory or potential for a field of work dedicated to understanding postatomic Nagasaki.

Can you tell us briefly about your current research project(s)?

I am currently working on a few projects. My next book will look at 1950s war films in Japan to understand how directors, actors, and score composers used their artistic medium to amplify political messages and promote memory activism. I am also writing an article on tattooing among the indigenous people of Taiwan under Japanese colonialism, and another article on the role of judo in cultivating ideas of the modern body at the turn of the twentieth century.